Peace. A gentle breeze coming down the creek between the mangroves and through the corridor of the house, rustling the drying wetsuits over the concrete porch, faint bird and insect songs from the mangroves all around us. A jutilla climbs down out of the trees into the dinghy tied off the porch to drink from the rainwater collected in the bilge. Sun emerging from scattered clouds on the horizon. A fresh day.

We clean up, load the gear onto the boat, say goodbyes, and board the boat for the long, sleepy cruise to Jucaro and another 5-hour bus ride.

Later: a great evening on the patio of the Hotel Nacional, where we stayed. Cohiba cigars and mojitos on the couches in the tropic evening air with our Irish friends.

Later: a great evening on the patio of the Hotel Nacional, where we stayed. Cohiba cigars and mojitos on the couches in the tropic evening air with our Irish friends.

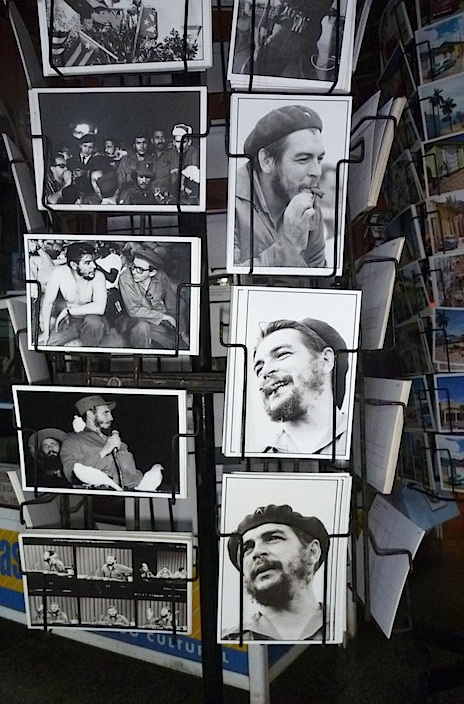

Only a week in Cuba. But in that time we’ve seen a glimpse of the natural world of Cuba, the strange aura of a land balanced between another long-gone time and an uncertain future, an island in the ocean of globalized society and commerce as well as in the more literal sense, isolated by American anger and frustration at not being able to dislodge what it perceives as a bush-league revolutionary 80 miles from its shore.

And that situation, via the stranglehold on western trade and the collapse of Soviet patronage over the last two decades in turn provide a fascinating window on the possible futures that might face us as the fossil fuel party finally winds to an end. Will our innumerable cars and machines wind down with it, and the great factories go quiet, as they’ve done here, standing with peeling paint and idle elevators as enigmatic monuments to a lost civilization like those of the Maya or the Romans in the countryside of their former empires?

Perhaps not—we have money, and some time at least, that were not available to Cuba when the party ended here. But do we have the will, and the foresight?

And Cuba is clearly a unique case (but isn’t everywhere?)—a nation that has been very consciously guided, partially successfully, by its leaders toward a society of equality and self-sufficiency and education over five decades, that has a small population relative to its land area, and that is less injured with the scars of rampant pillage of its resources than are many other places in what we call the developing world. Perhaps as a result of all these, it is a nation of problem solvers and eminently practical, competent people.

Life in Cuba goes on. And life goes back to the original source of all energy—the sun. Rank vegetation taking over, nourishing, if barely, the scrawny cattle and goats and horses and oxen and men and women that now laboriously break the earth by their own collective power, largely unaided by the dwindling stock of fuel stored up in the earth over hundreds of millions of years.

Is this medieval lifestyle the past for Cuba, beginning to fade as the society and economy open ever so slowly? We all felt during the trip that we were seeing something that would be hard to imagine in only a decade or so, that when the borders eventually open, as they inevitably will, it won’t be long till the place becomes Disneyworld for tourists.

Or is this the future for the rest of us?

Leave a Reply