Living here on the shores of the great Chesapeake Bay it’s sometimes challenging to keep the old chin up and maintain a positive attitude, what with the constant drumbeat of failing report cards, increasingly murky water, receding acreage of seagrass meadows, and ever growing list of once fabulously abundant fish and shellfish that are now difficult to make a living catching. The list goes on.

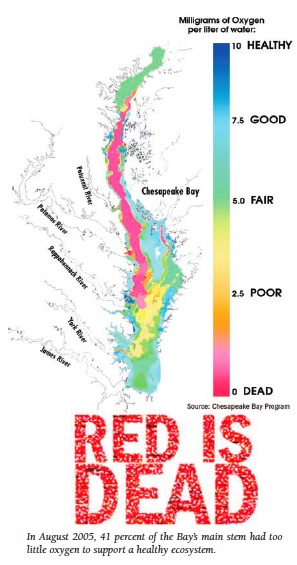

So it’s a happy event to read some good news for a change: new research shows the frequency of “dead zones”–areas of bottom with too little oxygen to support animal life–has been declining steadily. As reported by ScienceDaily:

So it’s a happy event to read some good news for a change: new research shows the frequency of “dead zones”–areas of bottom with too little oxygen to support animal life–has been declining steadily. As reported by ScienceDaily:

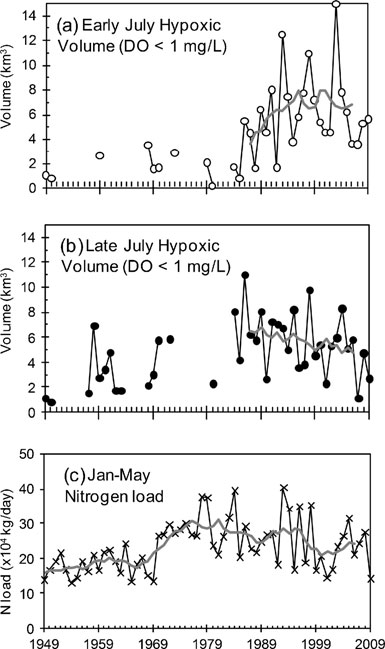

“The team found that the size of mid- to late-summer oxygen-starved “dead zones,” where plants and water animals cannot live, leveled off in deep channels of the bay during the 1980s and has been declining ever since. The timing is key because in the 1980s, a concerted effort to cut nutrient pollution in the Chesapeake Bay was initiated through the multistate-federal Chesapeake Bay Program. The goal was to restore the water quality and health of the bay.”

Hurray! Some good news at last. Reduction of point-source pollution, adoption of vegetation buffers along farms, and other management practices appear to be working.

But the story, typically, is not simple. The volume of hypoxic water in the Bay during early summer has actually increased over the last 60 years (see panel a at right). The new study found that this early summer spike was attributable to changing climate, not to runoff of pollutants. The key here appears to be stratification of the water column, that is, separation of an upper warm, fresh layer of water from a cooler, saltier layer at depth (think of plunging into a northern lake in late summer and the bracing chill that hits you about 4 feet under). The difference in density of the two water masses hinders mixing, and thus prevents life-giving oxygen in the atmosphere from getting down into the water near bottom. This becomes a problem when the water near bottom is full of dead algae that have fallen down out of the surface water and decayed leaves and stuff that’s washed down from the rivers, because all that stuff is food for bacteria that suck down oxygen when chewing it up. If oxygen can’t get from the atmosphere down to the bottom, you get a dead zone. The warming temperatures, and perhaps higher runoff of freshwater, in recent decades has strengthened this stratification and aggravated the dead zones in early summer.

Stratification is a particular problem when lots of nutrients wash into the water, as they have done increasingly from leaky septic systems, municipal wastes, and especially fertilizer runoff from farms as the Chesapeake watershed has been transformed from idyllic rural communities to suburban homes and convenience stores and what not over the 20th century. So the new work is somewhat surprising in concluding that controls on nutrient runoff have achieved some success in counteracting the decline (in late summer). Hats off for that.

Stratification is a particular problem when lots of nutrients wash into the water, as they have done increasingly from leaky septic systems, municipal wastes, and especially fertilizer runoff from farms as the Chesapeake watershed has been transformed from idyllic rural communities to suburban homes and convenience stores and what not over the 20th century. So the new work is somewhat surprising in concluding that controls on nutrient runoff have achieved some success in counteracting the decline (in late summer). Hats off for that.

Despite this cautiously optimistic news, it’s admittedly hyperbole to imply that the Chesapeake is being resurrected (my words, not theirs). The Bay that we know today is a sorry shadow of its former greatness. It is in fact among the classic examples of a shifting baseline. My favorite illustration of this is a report by Captain John Smith, the first European to leave an account of the Chesapeake back in 1607-1609 (no doubt there were pirates and other ne’er-do-wells that had been there before, maybe even the odd viking or Basque). Smith declared:

“Heaven and earth have never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation.”

I cannot for the life of me locate the source (and would be very happy to hear from any reader who can), but the story goes that Smith’s crew lost a cannon overboard in about 40 feet of water, but–not to worry–they were able to retrieve it. By hooking it with a grapple as they looked at it 4o feet down in a bed of seagrass!

To anyone familiar with today’s Chesapeake, this image is almost literally inconceivable. It’s rare to be able to see down 40 inches nowadays, and seagrass doesn’t live much deeper than that in the murky water of the new millennium. And if that’s not wild enough, imagine the lives of the Bay’s first watermen–Indians of the region poling around in dugout canoes spearing gigantic sturgeon, as shown in the iconic colonial painting used on the cover of Jeremy Jackson and company’s seminal Science paper.

To anyone familiar with today’s Chesapeake, this image is almost literally inconceivable. It’s rare to be able to see down 40 inches nowadays, and seagrass doesn’t live much deeper than that in the murky water of the new millennium. And if that’s not wild enough, imagine the lives of the Bay’s first watermen–Indians of the region poling around in dugout canoes spearing gigantic sturgeon, as shown in the iconic colonial painting used on the cover of Jeremy Jackson and company’s seminal Science paper.

So it’s good news that (late summer) hypoxia has been declining in recent decades, and we can celebrate that small victory. But let’s not forget what the formerly mighty Chesapeake, and the ocean generally, and the world once were. And perhaps could be again, in some sense, if we can muster sufficient ingenuity and will.

Leave a Reply