This week, a group of researchers published preliminary results from what will be the most comprehensive review of jellyfish population data. They say that there is not yet enough evidence to support any conclusions about a global upswing in jellyfish populations. “We are not at a point to make these claims,” says Robert Condon, a marine scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab in Alabama, who leads the group. “If you look at how that paradigm formed, it’s not based on data or rigorous analyses.”

Researchers studying jellyfish in the Gulf of Mexico and the Bering Sea now think that long-term natural climate cycles have an important role in controlling populations there. “Just seeing a lot of jellyfish does not say anything,” says Graham now. “People say, ‘Oh my God, the world is going to hell,’ but jellies form blooms. That’s what they’re supposed to do.” The challenge for researchers lies in separating normal fluctuations from those for which humans might deserve some of the blame. source

Scientists have been having a blast scaring the public about jellyfish for the last decade or so. But alas, the party is over: someone went and actually did some science and debunked this fun story.

It all started out so innocently. Scientists and others observed jellyfish “outbreaks” here and there. This grew into a concern about fisheries (it is funny how the same people that want to shut down commercial fishing, profess concern for the industry when it is threatened by things like climate change and jellyfish). Then scientists somehow decided that if jellyfish populations were exploding, it must be due to pollution! Or overfishing! Or climate change! We went from there to dire warnings about nothing being left to eat but jellyfish soup and jellyfish burgers. Eeeeeeek! Did you notice how those hollywood campaigns so effectively halted the human activities enabling the jellyfish hordes?! No? Oh right, scaring people doesn’t work. Dam you cognitive sciences!

Then along came a group of hard-headed empirical scientists to actually test the jellyfish-are-taking-over-the-ocean hypothesis with data. They secured funding from the NSF-funded National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, formed a working group and commensed to do science of the most eggheadishly-boring variety: no SCUBA diving, no boats, no electronic gizmos, not even any white lab coats. They built the ultimate jellyfish bloom database (AKA JEDI) by combining a large number of other existing databases.

The group recently published their first paper – sadly in the access-restrictive journal BioScience (Condon et al 2012*):

Questioning the Rise of Gelatinous Zooplankton in the World’s Oceans

During the past several decades, high numbers of gelatinous zooplankton species have been reported in many estuarine and coastal ecosystems. Coupled with media-driven public perception, a paradigm has evolved in which the global ocean ecosystems are thought to be heading toward being dominated by “nuisance” jellyfish. We question this current paradigm by presenting a broad overview of gelatinous zooplankton in a historical context to develop the hypothesis that population changes reflect the human-mediated alteration of global ocean ecosystems. To this end, we synthesize information related to the evolutionary context of contemporary gelatinous zooplankton blooms, the human frame of reference for changes in gelatinous zooplankton populations, and whether sufficient data are available to have established the paradigm. We conclude that the current paradigm in which it is believed that there has been a global increase in gelatinous zooplankton is unsubstantiated, and we develop a strategy for addressing the critical questions about long-term, human-related changes in the sea as they relate to gelatinous zooplankton blooms.

The paper starts by pointing out that in this context, the term “jellyfish” includes not only proper cnidarian jellyfish, but also ctenophores (comb jellies), and pelagic tunicates, e.g., salps. The technical science terms for all these beasts is “gelatinous zooplankton” which I will refer to as “jellyfish” for this piece. They go on to point out that population “blooms” are a distintive feature of this group. But have such blooms become more frequent as scientists suspect?

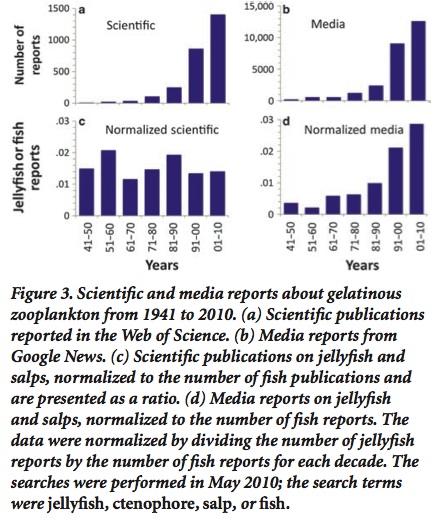

These reports partially led to the perception that modern gelatinous zooplankton blooms are increasing in number at a global scale.

The data at hand do not support the jellyfish-are-taking-over-the-ocean hypothesis. But the data are quite limited. We need more time series data (hello NSF, Congress, NOAA, is anybody listening?!)

The authors show that when normalized to the growth in oceanographic literature in general, scientific reports of jellyfish blooms have not increased in the literature. This is in contrast to media reports, which have exploded (Fig. 3)

Listen to an excellent and pointed interview about the jellyfish scare with lead author Rob Condon here

Including these excellent quotes: “There was no hard data to back up any of these claims” “he’s no some star wars nerd” “it was his wife’s idea” “This group of JEDIs…plowed through at least 30 years of datasets” “more harm than good comes out of these types of false claims”

*Condon et al. 2012. Questioning the Rise of Gelatinous Zooplankton in the World’s Oceans. BioScience 62:2 160-169

Leave a Reply