Tom Hooper ran ‘Finding Sanctuary’ one of four regional stakeholder-led projects to set up a new generation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) around the English coasts and offshore waters. In a guest post for Seamonster, Tom explains how England nearly got an ecologically coherent MPA network in 2013 and the emerging challenges of scientific evidence and a cash-strapped economy.

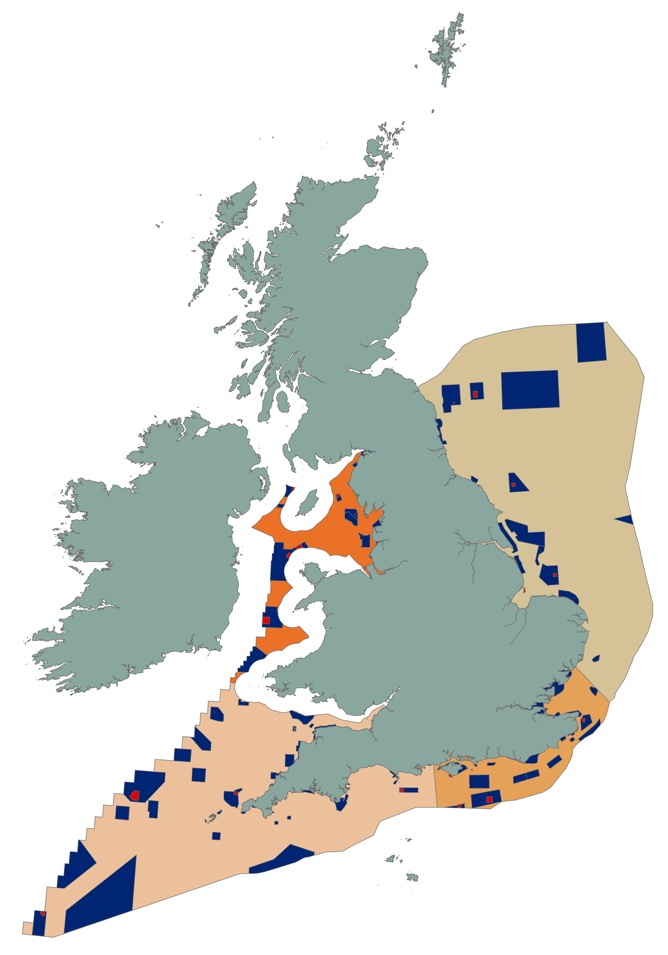

The aim of the new Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs) is to give England an ecologically coherent MPA network. This means that they were designed to complement existing sites to protect the full range of species, habitats and features in a region and they would be designed systematically as a network. As a key part of the Finding Sanctuary project, 42 different stakeholders such as fishermen, sea anglers and conservation organisations spent over 40 days in planning meetings to put forward recommendations for the design of the new MPA network.

Designing an ecologically coherent network of MPAs means that you need to set targets to answer questions such as how much needs protecting? At what scale? How far apart?

All over the world there are Conventions and aspirations for an ecologically coherent network, but until you put some specific targets together a design process is impossible. England’s conservation agencies, Natural England and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, put together the ‘Ecological Network Guidance’ a set of pragmatic targets and design guidelines that could be realistically used by stakeholders.

The process of gaining agreement between stakeholders was hard-fought and contentious and took two years, but 127 recommended MPAs were ultimately put forward around England in September 2011. Just over a year later only a quarter of these are likely to go forward; and the first ecologically coherent MPA network in mainland Europe seems like a forlorn hope for the time being. The reasons why are worth reflecting on, not least because they are a bit of a cautionary tale to those who may be embarking on their own design processes.

The outcome has been dismissed in some quarters as being ‘unscientific’; however in my mind we have to be more comfortable with the role of science in an MPA design process and what is reasonable in the marine environment. If you are going to work with stakeholders then you have to be able to synthesise information so that they are able to use data in a sensible way to make better decisions.

In our case, this meant large-format, laminated maps showing, for example, marine habitats, commercial fishing activity, pelagic frontal systems or species richness. We had a team of five planners and GIS specialists whose role was pivotal in supporting stakeholders in making decisions and giving them feedback in progress towards meeting their ecological targets.

One of the fundamental requirements of a process to design an ecologically coherent MPA network is that you work on the basis of best available science. In the terrestrial environment we are used to being able to count and describe in detail the species and habitats in a nature reserve. This degree of certainty is just not possible in the marine environment where our knowledge consists of small snapshots in a small proportion of the area.

A habitat map of our region might show well defined, brightly coloured patches of mud, shingle, rock and sand; but behind these maps the data points are actually very sparsely distributed. When you design a representative MPA network across a region, there will be sites distributed across a huge area and inevitably there will be a difference in the level of knowledge between, for example, a coastal seagrass bed and a mud habitat far offshore.

There is no benchmark for how much data needs to be assembled before an MPA can be designated. In my mind it should be proportionate to what can reasonably be expected to be available depending on how remote the site is.

This was a stakeholder process that used science; not a scientific process that used stakeholders – it doesn’t mean that the decisions have any less value or credibility.

Science is a tool that needs to be applied proportionately and should neither be used as a walking stick nor as a weapon. The process should be designed to fit the available evidence and not the other way around. In our case, the time has now come for politicians to make a decision and they seem to be using science as an excuse for delay and indecision.

The reality of an ecologically coherent network in England is also a victim of our ‘treble dip’ recession. It is not just about the cost of designating and enforcing 127 sites, but there currently seems to be little appetite for designating MPAs that will impact on commercial activities. Although MPAs could become an important part of sustainable rural economies and provide valuable ecosystem services these points have yet again failed to punch their weight in the final rounds of decision making.

Europe as a whole has a curiously cumbersome and atomised approach to marine conservation that focuses on the conservation of individual features rather than the integrity of whole areas. This is a hangover from the Birds and Habitats Directives, which seem to have been designed wholly for terrestrial conservation. They require evidence of the existence, health and vulnerability of each feature before management (protection) can be applied which poses a huge challenge in the marine environment.

A recent study for the European Environment Agency reported that the status of 40% of marine habitats and 70% of marine species is unknown. If all 127 MCZs are designated, they will introduce another 1200 features, each requiring rolling assessments of existence, health and vulnerability.

When money is tight and data is scarce, surely it makes more sense to work on a habitat rather than a species level and to follow examples set in California, Australia and many other locations outside Europe that achieves effective marine conservation by managing humans rather than trying to manage species?

Leave a Reply