I just published my first PeerJ Preprint here!

Abstract: Identifying the baseline or natural state of an ecosystem is a critical step in effective conservation and restoration. Like most marine ecosystems, coral reefs are being degraded by human activities: corals and fish have declined in abundance and seaweeds, or macroalgae, have become more prevalent. The challenge for resource managers is to reverse these trends, but by how much? Based on surveys of Caribbean reefs in the 1970s, most reef scientists believe that the average cover of seaweed was very low in the natural state. On the other hand, evidence from remote Pacific reefs, ecological theory, and impacts of over-harvesting in other systems all suggest that, historically, macroalgal biomass may have been higher than assumed. Uncertainties about the natural state of coral reefs illustrate the difficulty of determining the baseline condition of even well-studied systems.

“Preprints” are non-peer reviewed contributions to the scientific literature. Sort of like a book chapter or an invited review paper at TREE or Science. Specifically, they do not undergo pre-publication peer review, but there is (or can be) extensive and rigorous post-publication review, which to my mind can be a lot more important. For one, it isn’t (generally) anonymous. As we all know, many reviewers hide behind the shield of anonymity to trash the work of their peers and competitors or to prevent the publication of science that doesn’t agree with their views.

Physicists have used pre-peer-reviewed publication via the arXiv server for years decades, to share their ideas, preliminary findings, and draft manuscripts with their colleagues. Now us biologists have that option. PeerJ Preprints can be cited, show up on google scholar, are assigned a DOI, and can also be submitted elsewhere simultaneously for publication to most journals.

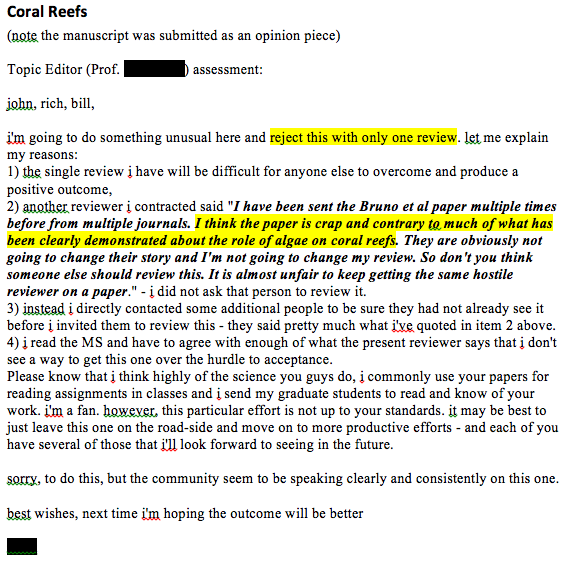

In our case, the manuscript has already been submitted and rejected by a number of journals, we think for both valid and invalid reasons. We decided to share the reviews as a supplement to our preprint. We masked the identity of the editors, but revealed which journal the reviews came from.

I think reviews are an important part of the scientific record and conversation. Having a rapid, open, and respectful back and forth would lead to much better science, better mutual understanding, less wasted time, much faster publication, etc. I strongly believe in transparency in the publication process and I think reviews of both accepted and rejected manuscripts should be accessible, e.g., on the journal website, in a blog, on FigShare, etc. The public and the scientific community should be able to see what the reviewers said about a paper, how the editor handled the reviews, and how the authors responded to them. Doing so would make the whole process more fair, by adding accountability for everyone involved.

Although a paper is often improved by peer review, the comments are sometimes overly critical, subjective, and far from constructive. This is especially true at the non-blue chip journals. I rarely get nasty reviews at the most “respectable” or competitive ecological journals, e.g., Ecology and Ecology Letters (although I get plenty of rejections from them). As an editor at Ecology, the reviews that I see are nearly always respectful and insightful. It is when I venture into coral reef science and the more specialized marine and conservation journals that the real nastiness and subjectivity comes out. Why? I don’t know. I don’t even know if it is real or just my perception. And since peer review is a closely guarded secret activity, there is no way to evaluate this objectively. But A LOT of people I talk to have had similar experiences, especially at the journal Coral Reefs, which took a big nose dive when Rolf Bak took over as editor.

Below is a selection of the more critical comments of our manuscript. I respond to some to point out the (probably obvious) fallacies in some of the reviewer arguments. The broader point here is not that our little paper is earth-shattering or even that it should be published, but rather that peer review, at least in this subfield, could be improved. (I will address how in a later post)

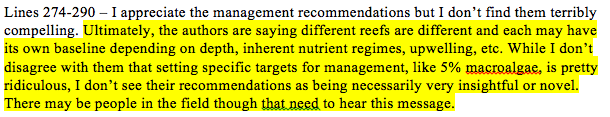

We did offer solutions in that we concluded with four recommendations. And the point of the paper was to describe and acknowledge the problem. In fact, there is no perfect solution. We will never know exactly what the real baseline is and that is the point. Since we really don’t know exactly what natural is (although we argue in the paper that we know what it isn’t) scientists need to tone down their criticisms of managers that don’t meet the scientists perceived local baseline, e.g., Pandolfi et al. 2005.

This comment also illustrates the general tone of editor and reviewer dismissals in coral reef science, especially at the less competitive journals like Marine Policy and Coral Reefs as well as a strong reliance on subjective judgment about “novelty and impact”.

We didn’t question the competence of elder colleagues. And Bill and Rich are not exactly spring chickens! Instead, this is an unavoidable consequence of using the two dimensional quantitative survey techniques that are the norm in coral reef science. Goatley and Bellwood (2011) demonstrated this in an elegant paper recently:

Abstract: Canopies are common among autotrophs, increasing their access to light and thereby increasing competitive abilities. If viewed from above canopies may conceal objects beneath them creating a ‘canopy effect’. Due to complexities in collecting 3-dimensional data, most ecosystem monitoring programmes reduce dimensionality when sampling, resorting to planar views. The resultant ‘canopy effects’ may bias data interpretation, particularly following disturbances. Canopy effects are especially relevant on coral reefs where coral cover is often used to evaluate and communicate ecosystem health. We show that canopies hide benthic components including massive corals and algal turfs, and as planar views are almost ubiquitously used to monitor disturbances, the loss of vulnerable canopy-forming corals may bias findings by presenting pre-existing benthic components as an altered system. Our reliance on planar views in monitoring ecosystems, especially coral cover on reefs, needs to be reassessed if we are to better understand the ecological consequences of ever more frequent disturbances.

Second, no, we do not think early researchers were dumb. We didn’t suggest they ignored macroalgae, we simply point out that when algae and other reef organisms are underneath a canopy-forming or branching coral, their true cover can be under estimated. Moreover, we didn’t argue that that macroalgae cover in the 1970s was 40% and we certainly don’t think this is the baseline (it varies from place to place but is likely much lower than this). Finally, it has been clearly demonstrated that damselfish were historically abundant on reefs and that often high densities are not due to the fishing of their predators.

Kaufman LS (1977) The threespot damselfish: effects on benthic biota of Caribbean coral reefs. Proc 3rd Intl Coral Reef Symp, Miami 1: 559–564.

Precht WF, Aronson RB, Moody RM, Kaufman L (2010) Changing Patterns of Microhabitat Utilization by the Threespot Damselfish, Stegastes planifrons, on Caribbean Reefs. PLoS ONE 5(5): e10835. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010835 We got this argument from several journals, including from Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (also an ESA journal); i.e., “this idea is dangerous!” – essentially advocating the suppression of data, speech, and ideas that are perceived as threats to reef conservation. Not professional and definitely not cool.

We got this argument from several journals, including from Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (also an ESA journal); i.e., “this idea is dangerous!” – essentially advocating the suppression of data, speech, and ideas that are perceived as threats to reef conservation. Not professional and definitely not cool.

Several reviewers also did not care for the contradictory nature of the evidence we presented, which was largely the point of the paper. This isn’t a clean story (as is so often the case in ecology). The macroalgal baseline is highly dependent on what evidence you consider.

As in the comment below and from several other reviewers, this reviewer argued we present selected information (that we cherry picked) without bothering to explain (provide a citation) what is missing. Why don’t editors ask for such references?

As in the comment below and from several other reviewers, this reviewer argued we present selected information (that we cherry picked) without bothering to explain (provide a citation) what is missing. Why don’t editors ask for such references?

A lot could be said about the subjective nature of the editors comments and of the comments from the second reviewer who thought our paper was “crap”. For one, it seems to me that the editor did in fact receive two reviews. But the thing that really strikes me is that the main argument is that we are wrong, whereas we heard from many other journals, e.g., Marine Policy, that we are right but everyone already knows this, nobody would disagree, we were not saying anything novel, etc. For example, here is a comment from MEPS reviewer #3:

A lot could be said about the subjective nature of the editors comments and of the comments from the second reviewer who thought our paper was “crap”. For one, it seems to me that the editor did in fact receive two reviews. But the thing that really strikes me is that the main argument is that we are wrong, whereas we heard from many other journals, e.g., Marine Policy, that we are right but everyone already knows this, nobody would disagree, we were not saying anything novel, etc. For example, here is a comment from MEPS reviewer #3: It is common to get such contradictory arguments from two reviewers from the same journal, e.g.;

It is common to get such contradictory arguments from two reviewers from the same journal, e.g.;

Reviewer 1: This is impossible! They are clearly wrong!

Reviewer 2: Everyone knows this! The study lacks novelty and impact!

Below are some of the comments from the one complete review from Coral Reefs:

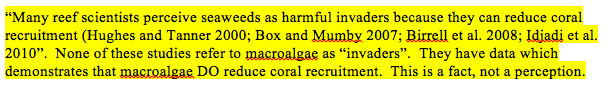

We did not argue otherwise and wrote “because they can reduce coral recruitment” and included four citations. It is a perception, however, that seaweeds are harmful invaders and generally bad for corals and reefs. Moreover, we don’t suggest this perception is wrong. This is one of many (willful?) misreadings of our text.

We did not argue otherwise and wrote “because they can reduce coral recruitment” and included four citations. It is a perception, however, that seaweeds are harmful invaders and generally bad for corals and reefs. Moreover, we don’t suggest this perception is wrong. This is one of many (willful?) misreadings of our text.

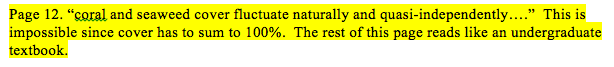

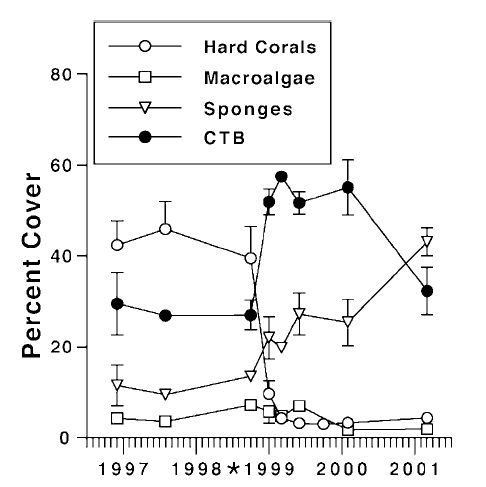

It is possible because there are organisms on reefs other than corals and algae, e.g., sponges, gorgonians, etc. Coral cover frequently varies without any response in macroalgae cover. Here is an example from Belize from Aronson et al 2002 (PDF), where coral cover crashed due to bleaching, urchins held the algae in check, and sponges became the dominant space holder.

It is possible because there are organisms on reefs other than corals and algae, e.g., sponges, gorgonians, etc. Coral cover frequently varies without any response in macroalgae cover. Here is an example from Belize from Aronson et al 2002 (PDF), where coral cover crashed due to bleaching, urchins held the algae in check, and sponges became the dominant space holder.

The same thing has been observed in countless other places, such as on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, where a collapse of coral cover has not been followed by a general increase in macroalgae.

This is typical of the strange comments from this reviewer. We didn’t suggest otherwise and in fact present a synthesis of the scientific literature.

We didn’t suggest that Connell used a time machine to survey reefs in the “pre-human past”. This is our sentence:

Reefs, like all communities, have always been disturbed. Even long ago in the pre-human past, reefs were dynamic, non-equilibrial systems and were not fixed in climax states of coral dominance (Woodley 1992, Connell et al. 1997, Vroom et al. 2006).

The citation of Connell et al. (and Woodley and Vroom), was for them having made the point that disturbance is natural on reefs. Is this not obvious?

The second sentence in the comment above is in response to this sentence from our paper:

In his long-term monitoring study of shallow reefs on the Great Barrier Reef, Connell documented repeated fluctuations of macroalgal cover between 15% and 85% due to natural disturbances and community succession (Connell et al. 2004).

Our intent was to point out that the cover of macroalgae can vary in time as well as in space. There are countless studies that document this and most of the reviewers argued this was so well-accepted there wasn’t any reason in pointing it out. Yet the Coral Reefs reviewer does not buy it and argues that on the intertidal reef crest, Connell found much lower algal cover. This is true, but we weren’t referring to the barren reef crest. We indicated we were interested in subtidal reefs here and only referred to Connell’s shallow subtidal data. This is the type of simple misunderstanding that could be clarified in a revised manuscript had we had the chance to do so.

Actually, Cote et al (2006) included 34 studies performed between 1977 and 2001. But very few (all of which are included in our paper) were from the 1970s or earlier.

Actually, Cote et al (2006) included 34 studies performed between 1977 and 2001. But very few (all of which are included in our paper) were from the 1970s or earlier.

We got the “why didn’t the authors cite the “other” studies that contradict their work” argument from several reviewers and journals. Reviewers didn’t bother to provide a citation, not out of laziness but because they don’t exist. This is common in peer review – unscientific criticism of science.

We got the “why didn’t the authors cite the “other” studies that contradict their work” argument from several reviewers and journals. Reviewers didn’t bother to provide a citation, not out of laziness but because they don’t exist. This is common in peer review – unscientific criticism of science.

We did in fact use all available quantitative data for the Caribbean (pre-1980) and on isolated central-Pacific islands (more recent data). We did not cherry pick. We didn’t exclude any data. And we thoroughly searched, especially for old Caribbean data.

So here we have serious accusations of scientific misconduct, and subsequent rejection of a manuscript, with no request by the editor – effectively the judge – to see some evidence of the crime. Just a passive acceptance of subjective, emotional criticism. Which is ironic given peer review is a dialogue among scientists about evidence, inference, and hypothesis testing.

The complete reviews and the responses we sent to the editors can be downloaded here from FigShare. Enjoy!

Leave a Reply