See updates below in red

Without empirical evidence that a population or guild of critters is declining it is pretty hard to understand why they are becoming scarce or to justify any remediation. This kind of work is essentially ecological bookkeeping. Or a form of empirical environmental journalism. I hear all the time from science colleagues that “we already knew that was happening” or “we already know enough to stop…”. Perhaps. But I think it is impossible to build consensus about a problem if you can’t demonstrate it exists.

Is coral cover changing?

The null hypothesis is that there is no change in coral cover (for a species or all corals). And the one-tailed alternative is that there has been a decline. If we find evidence for the latter, we ask what is the rate of decline, how does it vary with space and time, etc. Inevitably, it is messy and complicated. Many reefs recover from natural and anthropogenic disturbances. But slightly more do not. Thus in general, we see a slow, downward trend in coral cover nearly everywhere data are available.

There are hundreds of single or multiple site papers documenting change in coral cover on reefs (including coral recovery). For example, an influential classic is Hughes 1994 (Science PDF here): one of the first studies to demonstrate really drastic declines in coral cover. Terry resurveyed nine reefs off the north coast of Jamaica in the 1970s then again in the 1990s. The definition of a “phase shift”:

Below is a list of the key papers that either synthesize existing data or cover a large geographic range and many survey sites.

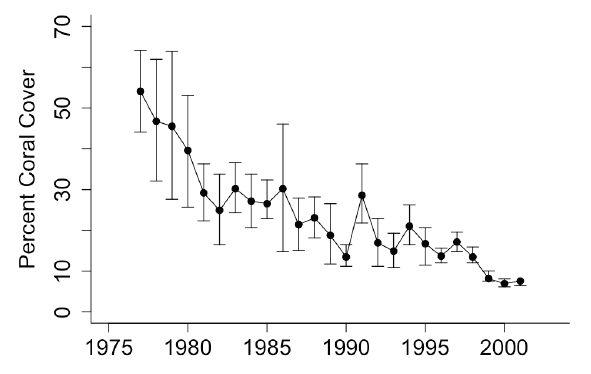

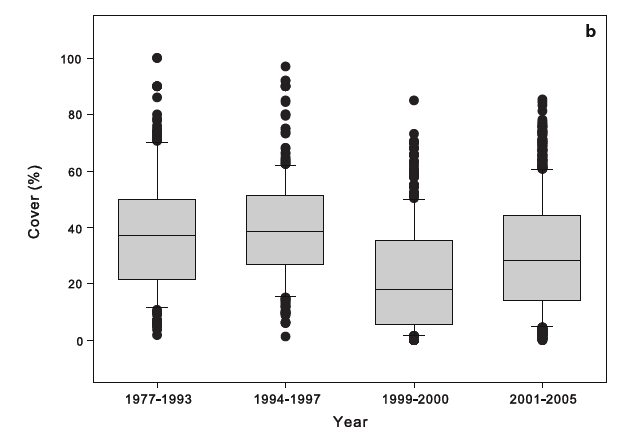

1) Gardner et al. 2003 (Science PDF here) and Cote et al. 2005. The first meta-analysis of coral cover loss across an entire region. The results really shocked the world and suggested the results of Hughes 1994 were at least somewhat general (but see Bruno et al 2009 PDF). The definition of grim:

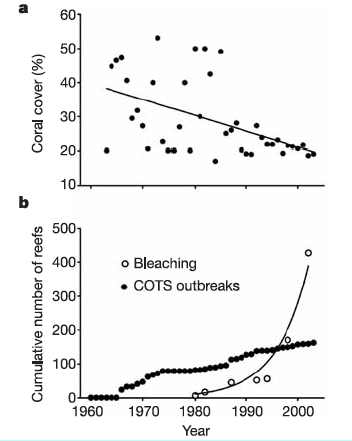

2) Bellwood et al. 2004 (Nature PDF here) analyzed coral cover surveys of the Great Barrier Reef for the first time and showed even the world’s “most pristine and best managed reef” was losing it’s corals:

3) Bruno and Selig 2007* (PLOS One link). We expanded on what had been done in these two studies by looking at coral cover trends across most of the Pacific ocean:

We compiled and analyzed a coral cover database of 6001 quantitative surveys of 2667 Indo-Pacific coral reefs performed between 1968 and 2004. Surveys conducted during 2003 indicated that coral cover averaged only 22.1% (95% CI: 20.7, 23.4) and just 7 of 390 reefs surveyed that year had coral cover >60%. Estimated yearly coral cover loss based on annually pooled survey data was approximately 1% over the last twenty years and 2% between 1997 and 2003 (or 3,168 km2 per year). The annual loss based on repeated measures regression analysis of a subset of reefs that were monitored for multiple years from 1997 to 2004 was 0.72 % (n = 476 reefs, 95% CI: 0.36, 1.08).

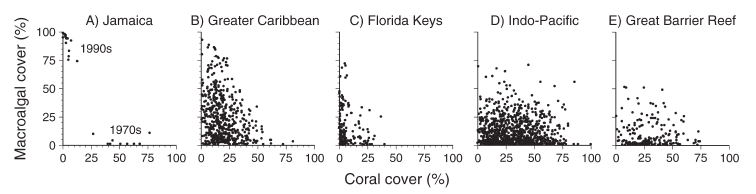

4) Bruno et al. 2009 (Ecology PDF here) analyzed 3581 quantitative surveys of 1851 reefs performed between 1996 and 2006 to determine reef state in terms of coral and macroalgal cover around the world. We found that the replacement of corals by macroalgae was less common and less geographically extensive than assumed. The figure below shows absolute living coral and macroalgal cover from the surveys in each region (the most recent survey from each site.)

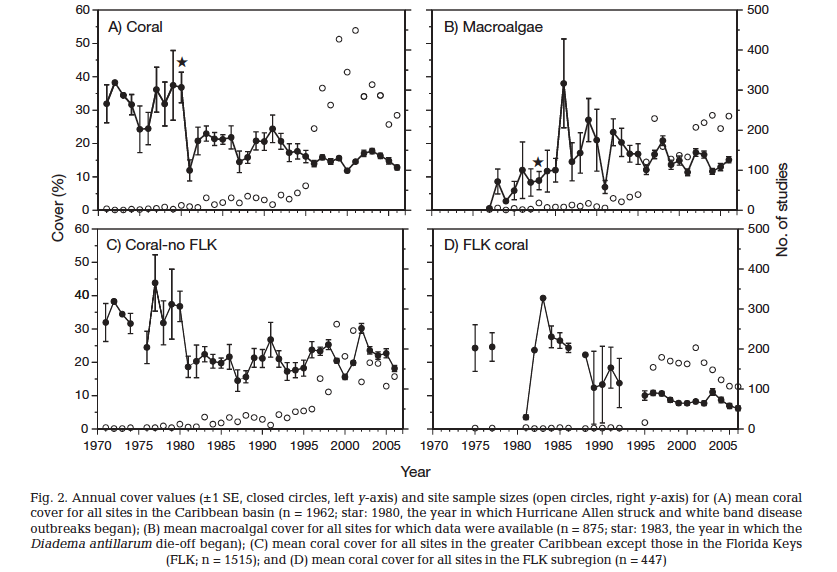

5) Schutte et al. 2010* (MEPS PDF here) We expanded Gardner et al., taking the data through 2006 and increasing the number of surveyed reefs by nearly 10X. The database included 3777 coral cover surveys from 1962 sites surveyed between 1971 and 2006. More grim, but signs of hope since coral and macroalgal cover had not changed much since the early 1980s, when the big drop in coral cover due to the white band disease outbreak occurred:

*note the data from these two papers was also used in Butchart et al. 2010 (Science PDF here)

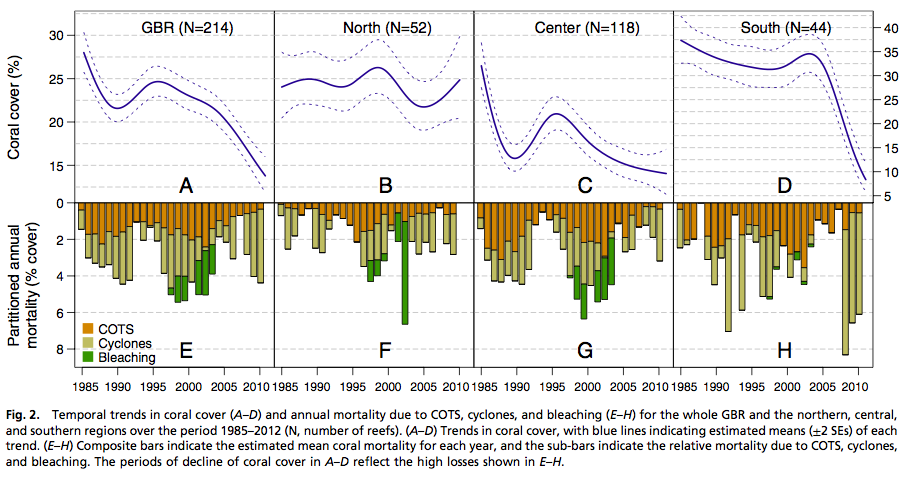

6) Death et al. 2013 – read all about this study documenting frightening coral loss on the GBR here. The AIMS GBR database on which this study was based has been used in a number of other coral cover trends papers, several of which wrongly argued that coral cover was not changing on the GBR, e.g., Sweatman et al which I criticized here and here PDF. Death et al. 2013 found:

“from 1985 to 2012, mean coral cover declined nonlinearly from 28.0% to 13.8%”

This is an incredible if sobering finding. It suggests that the mean coral cover of the GBR is no higher than the Caribbean average (which according to Schutte et al. 2010, was 16.0 ± 0.4% (n = 1547) from 2001 to 2005.

7) Ateweberhan et al. 2011 (Coral Reefs PDF): ~ 2000 surveys of 366 reef sites between 1977 and 2005 across the Indian Ocean. Although there was evidence for substantial coral loss due to the 1998 El Nino (via related bleaching), most reefs have recovered and overall, there is little to no evidence for long-term coral cover loss. (HT to Doug Fenner for reminding me of this study)

There are dozens of other reports on coral loss including the influential Status of Coral Reefs series put out by the IUCN (produced by the GCRMN in association with AIMS and then the RRRC until recently when IUCN took over coordination of the GCRMN) and the Reefs at Risk reports. These all have a quasi-quantitative quality to them and none are peer reviewed. They do all contain valuable information, but rarely really dig in and synthesize and analyze the data. Also note there are several ongoing projects that are amassing huge databases of tens of thousands of reef surveys and using cutting edge statistics and models to analyze the trends; e.g., the Jeremy Jackson-led IUCN project which published a preliminary report here (PDF). (See the final IUCN report here, but note there are numerous errors in it, including the authors flawed interpretation of the causes of coral losses).

Take home summary

As far as we can tell, the coral cover average of most regions is well below 20% and often closer to 10%. Therefore, I think we have lost at least 50% of living coral cover and more likely 60 or 70%. And in some regions quite possibly as much as 80-90%.

By not indicting whether I meant absolute or relative losses in this initial summary, Ive managed to confuse quite a few people and even facilitated yet another Fenner-Goreau email spat. Im sorry for not being more clear. I am generally critical of the use of relative loss values, as they can exaggerate seemingly innocuous losses, e.g., from 4% to 2% cover = 50% loss! So, I have attempted to clarify my summary below.

Based on current coral cover (10-20% in most regions) and assuming the coral cover baseline (the historical regional average, not the average of undisturbed reefs or the maximum potential cover) was ~ 50%, there has been an absolute loss of 30-40% (coral cover) and a relative loss of 60-80%. If you assume a higher baseline, the loss values obviously increase.

Caveats galore: Since we don’t know what the coral cover baseline is, it is impossible to say exactly how much coral we’ve lost. The views among coral reef scientists vary quite a lot about what is “natural” in terms of coral cover. A recent survey indicated that 50-75% was the most common answer (90/207 respondents) to the question “What is the Indo-Pacific baseline for coral?” Yet a sizable number of people answered 25-50% or >75%. The same is true for the Caribbean, where both 25-50% and 50-75% were popular answers. (read more about coral reef baselines here). Additionally, both the baseline and the loss varies from reef to reef and region to region. Many of the word’s reefs are very poorly sampled. So our estimates of recent and current coral cover are not especially precise and maybe not particularly accurate. Finally, it is complicated because we haven’t really lost entire reefs. Instead we have lost coral cover on them. Corals are being thinned, rather than entirely removed. This is different from habitat loss in rain forests, and many other habitats and the loss values do not translate perfectly.

I think I need to add a shout out to Reef Check in particular but also to all the other scientists and groups that collected and shared their survey and monitoring data with me and others. Thanks!

Gomez et al 1981: I should have mentioned this in my post initially. This is the mother of all large scale coral reef surveys. Ed Gomez and his team surveyed 619 sites in the late 1970s (download the PDF here).

Note, there are a few papers on trends for other metrics of “reef health” including Caribbean fishes (Paddack et al. 2009 PDF) and reef complexity (Alvarez-Filip et al. 2009 PDF). Yet much more of this type of work is needed. Why coral cover is changing is even more complex and fodder for another post.

Leave a Reply