Should Americans really eat more fish?

In a recent op-ed in the NYT titled “Let Us Eat Fish” Dr. Ray Hilborn, a fisheries scientist at the University of Washington, argued we should. Ray thinks that because some of the hundreds of fish populations harvested in U.S. waters appear to be recovering and approaching levels that will maximize their productivity, then we should increase our fish consumption. He went on to argue this would be an environmentally positive choice since it would reduce terrestrial habitat loss and pollution. Ray is known in marine ecology, my academic field, for pushing his colleagues to stick to the facts and avoid exaggerating environmental degradation – a message I support. Unfortunately, in his op-ed, Ray left out a few key facts himself and makes an argument driven more by personal bias than the scientific record.

Let’s examine the factual accuracy of six statements from Ray’s op-ed and then decide how well the evidence supports his overall argument.

1) “Over the last decade the public has been bombarded by apocalyptic predictions about the future of fish stocks”

I would categorize the recent science on fish and fishing a little differently. Rather than focusing on future fish stocks, this enormous literature has documented the past collapse of fish populations around the world and their current highly depleted status.

My research is focused on Caribbean coral reefs and there is no question that these systems are extremely overfished. I rarely see top predators on Caribbean reefs and only in no-take marine reserves do we ever see large numbers of fish or any fish larger than a dinner plate. This graph from Paddack et al. 2009 illustrates a broadly documented pattern: continued decline in fish abundance over the last several decades across the Caribbean basin:

Change in reef fish density across the Greater Caribbean. Bars are 95% confidence intervals. From Paddack et al. 2009. Based on a meta-analysis of fish surveys performed with SCUBA on 318 reefs, ie, fisheries independent data. Sample sizes are given in parentheses and represent the number of individual fish density estimates included in the analysis for each temporal grouping.

Change in reef fish density across the Greater Caribbean. Bars are 95% confidence intervals. From Paddack et al. 2009. Based on a meta-analysis of fish surveys performed with SCUBA on 318 reefs, ie, fisheries independent data. Sample sizes are given in parentheses and represent the number of individual fish density estimates included in the analysis for each temporal grouping.

This Jamaican fish trap illustrates a phenomena that is pretty-much Caribbean-wide. The fish inside are not bycatch; they are the target fishery. These reefs have very few other fish – everything else was fished to local extinction decades ago:

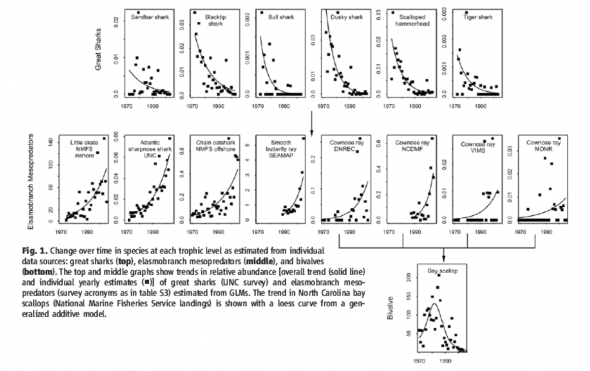

Here is another example of fisheries-independent data collected and analyzed by my UNC colleagues Dr. Pete Peterson and Dr. Frank Schwartz (the figure is from Myers et al 2007):

Frank has been assessing the abundances of sharks off of North Carolina for over 40 years and like many similar studies, his work documents the rapid decline in top predators like tiger and bull sharks due primarily to sport fishing. This freed rays like the cownose ray from predation and caused an increase in their abundances that in turn decimated our scallop fishery, ie, large sharks eat rays and rays eat scallops. So one key function of sharks was to “protect” scallops from overconsumption by their own predators. Ecologists call this indirect facilitative relationship a “trophic cascade”. Such cascading effects are ubiquitous in nature and are just one of countless ways species are bound to each other in a complex web of interactions.

Frank has been assessing the abundances of sharks off of North Carolina for over 40 years and like many similar studies, his work documents the rapid decline in top predators like tiger and bull sharks due primarily to sport fishing. This freed rays like the cownose ray from predation and caused an increase in their abundances that in turn decimated our scallop fishery, ie, large sharks eat rays and rays eat scallops. So one key function of sharks was to “protect” scallops from overconsumption by their own predators. Ecologists call this indirect facilitative relationship a “trophic cascade”. Such cascading effects are ubiquitous in nature and are just one of countless ways species are bound to each other in a complex web of interactions.

There are countless papers and graphs documenting the same pattern over and over again all around the world. But I don’t think any graph is convincing as a picture (and a time capsule) like the ones Dr. Loren McClenachan dug up in the Monroe County Library in Key West, Florida. The images document the striking decline in fish size on a single dock over time:

[cincopa AcJAtlazc91R]

2) “Subsequent research, including a paper I co-wrote in Science in 2009 with Boris Worm, the lead author of the 2006 paper, has shown that such warnings were exaggerated”

Really? Well… no. Unfortunately, Worm et al 2009 did not conclude “such warnings were exaggerated”. Instead, the Abstract and Conclusion sections of the paper include statements like:

“63% of assessed fish stocks worldwide still require rebuilding, and even lower exploitation rates are needed to reverse the collapse of vulnerable species”

“Unfortunately, effective controls on exploitation rates are still lacking in vast areas of the ocean, including those beyond national jurisdiction”

“Ecosystems examined in this paper account for less than a quarter of world fisheries area and catch, and lightly to moderately fished and rebuilding ecosystems comprise less than half of those. They may best be interpreted as large-scale restoration experiments that demonstrate opportunities for successfully rebuilding marine resources elsewhere.”

3) “The overall record of American fisheries management since the mid-1990s is one of improvement, not of decline…Few if any fish species in the United States are now being harvested at too high a rate, and only 24 percent remain below their desired abundance“

I agree with the first statement: there has been progress in the management of some fisheries in U.S. waters, however, why Ray concludes that “Few if any fish species in the United States are now being harvested at too high a rate” is unclear. The NOAA report Ray linked to includes this map of species currently “overfished” is the U.S.:

That is quite a few ecologically and commercially important species that NMFS categorizes as overfished.

As David Newman points out “Hilborn is also wrong when he claims that “few if any fish species in the United States are now being harvested at too high a rate.” In truth, 20 percent of species tracked as part of the government’s Fish Stock Sustainability Index – the same source cited by Hilborn – are still being fished at too high a rate, and thus subject to overfishing.”

Talking Fish agrees; “[Hilborn’s] piece correctly states that populations of haddock and redfish have increased dramatically in New England, it neglects to mention that many other stocks managed as part of the Northeast multispecies groundfish complex are still subject to overfishing and/or are overfished, including Atlantic cod, Atlantic halibut, white hake, windowpane flounder, winter flounder, witch flounder and yellowtail flounder. The rebound of haddock and redfish is excellent news, but it does not speak for the state of the marine ecosystem as a whole.

Also see Eric Heupel’s excellent post explaining the Fishery Stock Sustainability Index (FSSI) from which these assessments were derived. He argues that the most recent FSSI fisheries grade is a D; not exactly something to gloat about.

It is also important to consider that when a fisheries scientist tells you a population is overfished, they mean fishing pressure is too high to maximize productivity, i.e., reducing fishing would increase production and catch, the optimal fisheries density generally being roughly half the populations natural density. This is probably not the definition of “overfished” that came to many readers minds and not one ecologists or conservation biologists would use. I’d consider a population “overfished” when its numbers are reduced to a degree that its function in an ecosystem is significantly altered. This nearly always occurs long before a population is commercially “overfished”. Furthermore, many fisheries scientists recognize the need for more conservative catch limits, as Ray and his co-authors argued in their Science paper (Worm et al 2009): “in fisheries science, there is a growing consensus that the exploitation rate that achieves Maximum Sustainable Yield (uMSY) should be reinterpreted as an upper limit rather than a management target. This requires overall reductions in exploitation rates”

I understand that people need to eat and have an income, but Ray is an exception among scientists in continuing to argue that the ecological function and ecosystem impacts of fishing should not be taken into account when determining optimal population sizes and catch limits.

Ray’s view of wildlife as a mere resource waiting for consumption is on display throughout his essay with quotes like this; “Rebuilding, however, has come at a cost: to prevent overharvesting and protect weak species, about 30 percent of the potential sustainable harvest from productive species (those that can be harvested at higher rates) goes untapped“

Finally, the status of most fish harvested in U.S. waters is not even assessed by NOAA and don’t show up in these statistics. For example, none of the six clearly overfished (by any definition) sharks in the Myers et al 2007 study (described above) do. In Puerto Rico, there are dozens of fish species that are so depleted they are functionally extinct from nearshore environments, yet only grouper and conch appear to be on NMFS’s radar. There are also many species, like the North Atlantic Right Whale that are no longer fished but have not recovered from earlier over-explotation that are not considered in Ray’s analysis. Other species, like the Loggerhead Sea Turtle, that are the indirect victims of fishing (adult turtles get caught up in fishing gear and drown) don’t make the list either. Neither do invertebrates, many of which have been fished to ecological extinction (and are far below MSY), including abalone in California, sea urchins in New England, and blue crabs and horseshoe crabs along Atlantic shores, lobsters in the southeastern U.S., etc.

4) “On average, fish stocks worldwide appear to be stable…”

This is unlikely to be true, although it is difficult to assess since the data are dodgy or nonexistent for most of the world’s harvested populations. Recall, that in their analysis of the state of the world’s fisheries, Ray and his coauthors were only able to assess 25% of world fisheries area and catch, with almost no data for the tropics and most of the developing world. The fisheries-independent data that do exist (such as the meta-analysis by Paddack et al. 2009, also see Newman et al 2006 and Stallings 2009) certainly don’t jibe with this statement. As Talking Fish points out, “it is difficult to understand how a scientist of Hilborn’s stature could come to a conclusion about the overall health of the world’s fish populations given his concession in the op-ed that little is known about the stock status of fish populations in ‘much of Africa and Asia.’ “.

Yet Ray’s points gets us to the real heart of the matter: most of the seafood Americans eat is imported, therefore, the state of US fisheries shouldn’t influence our seafood consumption. By arguing we should eat more fish, what Ray is really saying is that we should be eating more of other people’s fish. In 2009, NOAA reported that 84% of the seafood consumed in the US was imported and this figure is growing.

In 2009 the U.S. imported 5.2 billion tons and exported 2.5 billion tons of seafood; a huge trade deficit that has global ecological and socioeconomic impacts. Like our spending deficit, China meets nearly a quarter of our seafood deficit. The rest of Asia and South America make up the rest:

I suppose a more reasonable (and factually supported) argument would have been that since the management of US fish stocks seems to be improving, Americans can begin to eat more American fish. The problem is, this would be impossible to do in practice for the simple reason that nobody would have any idea where the fish they were buying and eating were coming from. You don’t even know what species you are really consuming most of the time due to fraud in the sea food industry.

5) “if fish are off the menu, we will likely eat more beef, chicken and pork. And the environmental costs of producing more livestock are much higher than accepting fewer fish in the ocean: lost habitat, the need for ever more water, pesticides, fertilizer and antibiotics, chemical runoff and “dead zones” in the world’s seas”

First, nobody is arguing that fish should be “off the menu”. Second, I doubt there is a direct relationship between the consumption of fish and beef, chicken and pork. Third, these environmental costs, eg, dead zones, are due primarily to the farming of plants like corn and oil palm and not to livestock agriculture (although there are some important exceptions like deforestation for beef production in Brazil). Fourth, there are enormous environmental costs of fishing that Ray apparently is not aware of. These indirect impacts of harvesting and farming (via aquaculture) fish leads to precisely the impacts Ray mentions, i.e., habitat loss, chemical pollution, etc.

For example, as Eric points out over at DSN, bottom trawling – the method of choice for catching bottom fish in New England – is highly destructive. The method essentially entails dragging a weighted net across the sea floor; it is effective, but catches and kills indiscriminately and also destroys essential fish habitat (imagine cutting down a forest to catch a squirrel).[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bUHcD_jTgVA[/youtube]

Bottom trawling and other forms of net fishing also have lots of “bycatch“, a polite term for species, i.e., animals, that are accidentally caught and then thrown overboard usually after they sufficate on deck. In some fisheries, the ratio of bycatch to catch (of targeted species that are kept) can be 10:1 or higher, particular in the wild shrimp fishery where bycatch ratios can reach 20:1 and consist of endangered species like sea turtles. The photo below is the catch from a shrimp trawl; hard to see any shrimp in that pile of flesh isn’t it.

Speaking of shrimp, the top three seafood imports in 2009 as recorded by NOAA were shrimp (1.2 billion tons), tuna (718 million pounds) and salmon (501 million pounds). Nearly all of that shrimp comes from man-made ponds (shrimp farms) in Asia and Ecuador created by cutting down coastal mangroves. This is the primary reason roughly half the world’s mangroves have been lost over the last several decades.

The image above is of Muisne, Ecuador, where roughly two thirds of mangroves forests have been replaced by shrimp farms.

The image above is of Muisne, Ecuador, where roughly two thirds of mangroves forests have been replaced by shrimp farms.

A large majority of our third most popular import, salmon, are also farm-raised. Salmon farming causes serious environmental problems as well and negatively effects wild salmon populations we are trying rebuild and prevent from going extinct.

Finally, as in the shark-ray-scallop case I described above, substantial reductions in key species leads to community shifts and the loss of ecosystem functioning that hurt us economically and wreak ecological havoc in the ocean ecosystems.

Again, people clearly need to eat and fish protein is an important component of the diet of hundreds of millions of us. Yet to argue that fishing is any less destructive than terrestrial agriculture is misleading (to put it lightly).

6) “Suddenly, that tasty, healthful and environmentally friendly fish on the plate looks a lot more appetizing”

Tasty? For the most part (although I am not a big fan of “monkfish“, maybe unfairly judging the taste by the appearance). Healthful? Sure, some fish, such as salmon, are very healthy to eat (in moderation). But not farmed-raised shrimp from China and lots of other fishes and seafood species. Environmentally friendly? Not exactly. There are a few species that are wild-caught (not farmed) and harvested sustainably with “minimal” ecological impacts (yup, there’s an app for that), but those are the rare exception.

The bottom line

Rays’s argument is not supported by the facts. He thinks about seafood consumption with a myopic national view and appears to be unaware of where most of our seafood comes from and what the social and ecological impacts of importing fish from developing nations is in those regions. (Ironically, Ray and his colleagues argued for a “global perspective on rebuilding marine resources” in Worm et al (2009)).

I am not arguing people shouldn’t eat fish. I eat wild salmon roughly once a month and I love it. But I don’t think we should be gobbling up others people’s fish just because we have the economic leverage to do so. In addition to depriving them of protein in their own diets, we are indirectly degrading their marine environments and increasing our own carbon footprints by transporting seafood internationally.

[Editorial postscript: This post generated a lot of email responses and conversation, which have been collated together and can be read at SeaMonster’s “Forum on fish, food, and people”]

Leave a Reply