Day 7: Thursday 2 June

Done. All over now but the last dregs of clean-up and packing. Five days in the “Gardens of the Queen”, and what a time it’s been. A journey back in time in both the state of society and of the Sea. In the last five days we’ve become accustomed to sharks cruising all around us, a ten-foot crocodile our regular dinner companion, a tarpon hanging around under the stilt house, sea turtles breaching while underway, clouds of fish and generally the most unspoiled reefs I’ve seen anywhere in the Caribbean. And the people—wonderful.

This morning we dove at El Peruano—a reef without sharks. But the rest of the scene made up for it: great swirling clouds of creole wrasses along the reef edge, black durgons and yellowtail snappers and young bar jacks frantically picking at the invisible plankton drifting in from the open ocean. A small squadron of cero mackerel coming through, turning and pulsating and diving like a single organism. It was magical.

[cincopa A8EAkqq410N-]

Seeing these dense aggregations of animals hanging at the edge of the reef reminded me of hearing this phenomenon described as the “wall of mouths” — a gauntlet of predators facing any unsuspecting larva or plankter that happens to drift in from the ocean. It also helps illuminate one of the age-old paradoxes of corals reefs, known since Darwin’s time–that such exuberant diversity and abundance of life can exist in regions of the ocean that are essentially deserts. The clear blue water so inviting to us is a sign that there are vanishingly small concentrations of the dissolved nitrogen and other minerals that plants need to make a living and to support the rest of the food web. How can this be?

One answer is that much of the nutriment that supports reef organisms comes ultimately from outside the reef via stuff wafting in from the ocean. Although the concentration of stuff (whether plankton or nutrients) in blue oceanic waters is small, the flux can be substantial (flux = concentration x rate of delivery) because of the constant flow of water over the reef, driven by the reliable trade winds. The wall of mouths knows this and that’s why these fishes hang out here.

The famous ecologists (and brothers) E.P. and H.T. Odum (who has a posthumous Facebook page! What next?) figured out the outlines of this story back in the 1950s at Enewetak Atoll in the mid Pacific. The then-new Atomic Energy Agency was funding scientists to study the remote Pacific islets and atolls that the US had blown to smithereens during the atomic testing program of World War II to figure out what happens to habitats, animals — and of course people — after such a cataclysmic onslaught. And what happens to the radiation. The Odums managed to squeeze some pioneering research on the ecology of coral reefs and of ecosystem generally out of those sinister origins. Their classic monograph is available via open access through JSTOR here.

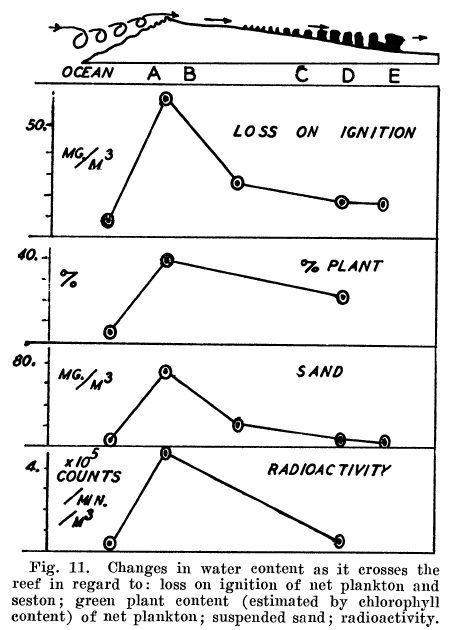

The figure at right (from the days before Powerpoint, Adobe Illustrator, and so on) shows how the chemistry of water changes as it washes from the blue ocean over the reef and off the back end. In this case very little organic matter came in from the ocean — most of it was presumably produced by algal photosynthesis on the windward side of the reef and mixed into the water by waves, where it then flowed back and nourished the animals of the back reef and lagoon. So how do the algae here maintain high rates of production in the desert? As Walter Adey showed many years ago, this is explained by the combination of steady current over the reef (again high flux of nutrients despite low concentrations) and turbulence from the constant wave action, which mixes up the water and makes it easier for algae to absorb the nutrients from the water. By the time the water flowed off the leeward end of the reef, the organic matter had been eaten up. Thus, the coral reef is a very efficient ecosystem, using up most of the organic matter it produces and exporting very little into the surrounding ocean.

Back to the lab. A sweaty, buggy afternoon on the rockpile, cracking up dead coral rock. One of the characteristic denizens of the wave-washed forereef is the prisoner shrimp (I just made that name up but I think it’s pretty good), Alpheus simus, an ungainly and even grotesque creature that spends its life trapped with its mate in a hollow chamber in the coral rock of the reef crest, connected to the outside world only by a sieve-like series of perforations in the rock through which it extends its long, worm-like second legs to pick algae and what not from the surface of the reef rocks in between crashing waves. If you pound the reef rock with the butt of your knife you can hear the crackling of thousands of these guys riddled in the rock and snapping their claws. Just one of thousands of bizarre and fascinating organisms that haunt the crevices and holes of this amazing environment, and which even most marine biologists never see.

Back to the lab. A sweaty, buggy afternoon on the rockpile, cracking up dead coral rock. One of the characteristic denizens of the wave-washed forereef is the prisoner shrimp (I just made that name up but I think it’s pretty good), Alpheus simus, an ungainly and even grotesque creature that spends its life trapped with its mate in a hollow chamber in the coral rock of the reef crest, connected to the outside world only by a sieve-like series of perforations in the rock through which it extends its long, worm-like second legs to pick algae and what not from the surface of the reef rocks in between crashing waves. If you pound the reef rock with the butt of your knife you can hear the crackling of thousands of these guys riddled in the rock and snapping their claws. Just one of thousands of bizarre and fascinating organisms that haunt the crevices and holes of this amazing environment, and which even most marine biologists never see.

Later . . .

Right before my eyes as I sit on the back deck, a disturbance in the water—some animal is dashing around in quick circles after a minnow. Turns out to be a cormorant, just under the surface, who comes up with the quarry in its beak. First time I’ve seen that, and at close range.

Leave a Reply