Marine reserves won’t save the oceans. Not now. Maybe never.

So say Camilo Mora and Peter F. Sale in their paper published today. If they’re right, and if people listen, it’s going to stir things up big-time in the conservation world.

Nature reserves, parks, protected areas… whatever you want to call them… those bits of the planet we set aside for the wild, are reckoned by many to be the holy grail of conservation. They give us a triumphant win-win solution: help ourselves – help the planet.

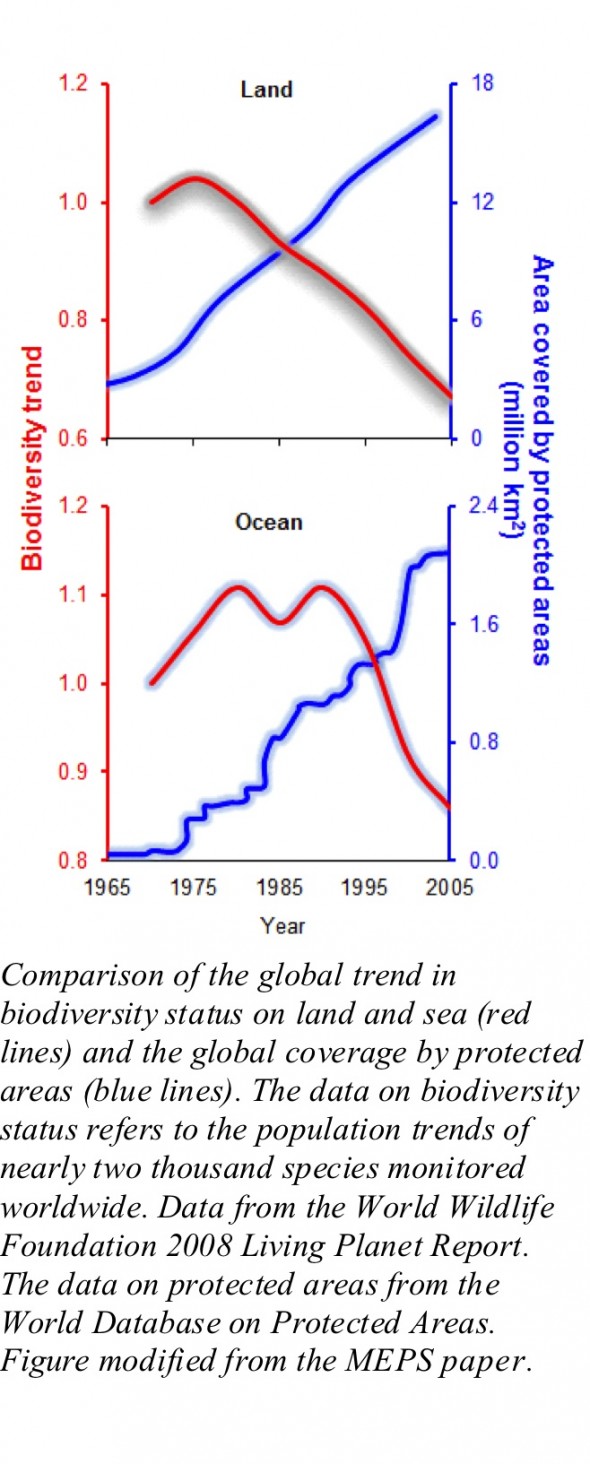

But, according to Mora and Sale, protected areas on land and in the sea are failing to deliver on all those conservation promises. Even though we’re protecting more of the planet than ever before, wild species are still in decline. Local success stories are being drowned out by a global slump in biodiversity.

Dr Sale said:

“Protected areas are very useful conservation tools, but unfortunately, the steep continuing rate of biodiversity loss signals the need to reassess our heavy reliance on this strategy.”

So what to make of all this?

Here are Seamonster, we’re marine ecologists. We love the oceans but are driven ultimately by science and not simply by what we believe to be true. Mora and Sale make a lot of really important points. But they also chose a particular standpoint from where they declare their verdict: they took a giant a step back, picked up a huge brush, and painted a coarse picture of the state of the planet and our efforts to protect it.

What details are we missing here?

OK – first up – the paper. What did Mora and Sale do and what do they say? It’s a big, dense paper, definitely worth reading (and it’s open access, so anyone can take a look), and I’m not going to go through it in detail here. But in brief…

What they did:

They got hold of data on 1) the total size of protected areas since the 1960s and compared it up against 2) the living planet index – a measure of how vertebrate species are getting on worldwide.

They did the same thing with protected area coverage and percent coral cover for reefs in the Caribbean and Indo-Pacific.

What they found:

Over time, both the living planet index and coral cover go down at the same time as coverage of protected areas goes up. i.e. more protection = worse state of the planet = protected areas aren’t working.

And they make some very important points:

There aren’t enough of protected areas, they lack connectivity, conservationists are too eager to proclaim their benefits, they cost too much, and they clash with human development targets.

And then there are all those global problems that pay little or no attention to invisible boundaries drawn across land and sea – global warming, ocean acidification, and alien species being the key suspects.

Mora and Sale waggle a cautionary finger, pointing out that oftentimes protected areas may seem to be working when really they aren’t. Among the evidence for this is Willis et al’s 2003 study that argues for a more robust interpretation of ‘statistically significant’ effects of marine reserves.

They also point out the problem of scale, that “variations in richness, abundance, or diversity are usually scale dependent and more pronounced at larger spatial scales.”

And it is on the issue of scale that I feel most uneasy.

This is emphatically a big-picture study. Mora and Sale are essentially trying to take the biological pulse of the planet, a proxy for the messy, complicated business of ecosystems and biodiversity (a similar sort of aim is underway with the Ocean Health Index project – with a team hunting for the Dow Jones of the oceans). And they’re using that health proxy to show that the medicine we’re currently prescribing isn’t working.

Does this give us a true understanding of what is going on? What do we miss from the nuance of the local?

But maybe that is their point – local won’t matter if we don’t do something about the big problems. If we don’t figure those out, we may as well give up on the beautiful but small projects that save a coral reef here, a mangrove forest there.

Protected areas are the backyard solution to conservation problems. They are the main way to tackle issues at a local, or even regional scale. Done properly, marine protected areas are the way to boost local fish stocks and catches, prevent coral reefs from being bashed apart by anchors and dynamite, and empower communities and give them a sense of ownership and responsibility for their local piece of coast.

At least that’s what most of us have thought until now.

Take away this reassuring, not-exactly-rocket-science approach to conservation, and we’re being forced to look deeper, to gaze into the fearsome, nebulous problems of human population growth and the massive footprint we are treading all over the planet’s natural resources. Where and how do we start tackling those problems?

Mora and Sale are right to question our beliefs in land and marine reserves. If this encourages people to assess reserves properly and figure a way of paying for them, then good. But I only hope this study won’t create a backlash against protected areas. I fear anti-reserve lobbies will jump on these findings and use them to bolster resistance against programmes that are pushing hard for protection – like the UK network currently in the grass roots planning stages.

This study isn’t saying we should give up on marine reserves. But it suggests that they’re being used as the Elastoplast of ocean conservation, a way of making ourselves feel better, when in fact we aren’t addressing the underlying causes. But aren’t protected areas vital to keep things going, to give ecosystems the best chance of hanging in there, while we crack the bigger problems of climate change and acidified seas?

We’d love to hear what you think.

Leave a Reply