In a new paper – that got a lot of media coverage – Smith et al 2016 quantified benthic reef composition “across 56 islands spanning five archipelagos in the central Pacific”.

I think it’s an admirable project and an interesting data set, and there is a lot to like about the paper. However, some of the main interpretations, particularly in the press coverage, are off the mark.

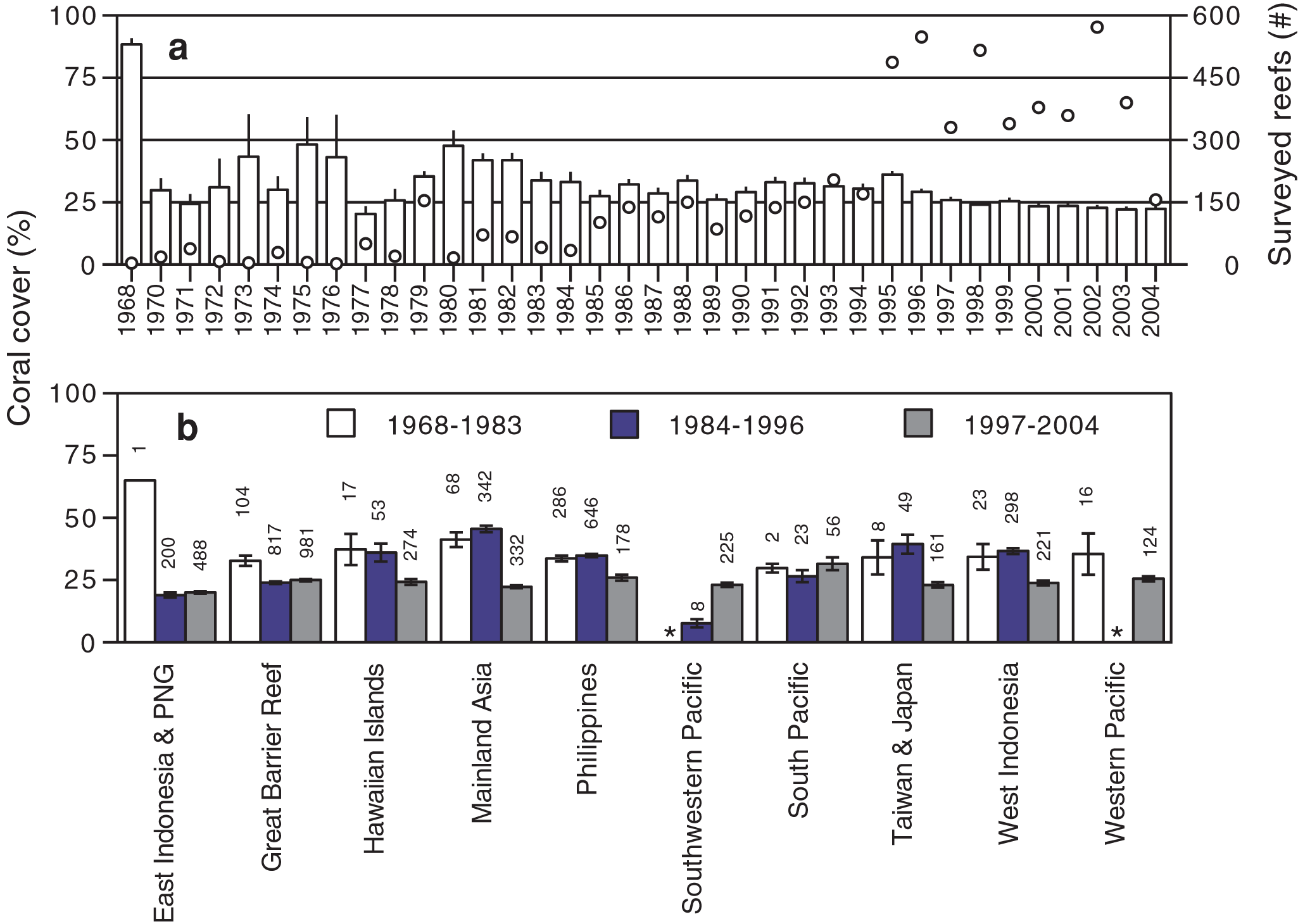

Although average coral cover was greater on reefs adjacent to uninhabited islands (24 vs 15%), this difference was non-significant; a key fact ignored or downplayed in the press. More importantly, the average coral cover of the human-dominated reefs Smith et al. surveyed isn’t representative of reefs in the region. Numerous synthesis of large survey and monitoring programs indicate the coral cover average used in Smith et al. for comparison to the uninhabited reef atolls is strangely low. This broader work also indicates the observed coral cover on uninhabited reefs isn’t at all exceptional. For example, mean coral cover across the Indian Ocean was 31% (2001-2005, Ateweberhan et al 2011), and in most subregions, cover was greater than the isolated reef average of 24% reported in Smith et al, e.g., Western Australia: 34%, Mozambique & South Africa: 28%, South Western Indian Ocean Islands: 36%.

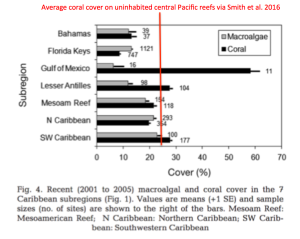

The 15% value reported by Smith et al. is even lower than the average across the Caribbean – a highly disturbed and degraded region that lacks plating acroporiid corals (thus the central Pacific baseline is almost certainly 10-20% higher). And the value of 24% for uninhabited central Pacific reefs is a common, nearly universal subregional average these days, e.g., as seen across the Pacific (via Bruno and Selig 2007):

And even across most the Caribbean (Schutte et al 2010):

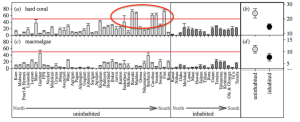

Some of the reefs Smith et al. surveyed clearly have very high coral cover:

But the same is true of the broader Pacific, Indian ocean, and Caribbean, e.g., see this figure.

And I agree, their data indicates there is plenty worth preserving and fighting for and in that sense constitutes good news. But that finding and message is true of every regional synthesis of coral loss I’m familiar with – it isn’t particular to highly isolated reefs and regions. All regions have reefs and areas with especially high coral cover and far more fishes. It isn’t objective to attribute the coral cover values on the reefs in Smith et al. 2016 to isolation and the absence of people given similar observations are made around the word, often adjacent to developed coastlines.

In fact, to me, the lesson of Smith et al. is that even our most remote reefs are highly impacted and sensitive to (and not resilient to) ocean warming and subsequent bleaching, disease and coral loss. Just look what’s happening on the highly isolated northern Great Barrier Reef this week. Although isolated reefs could plausibly recover from bleaching more quickly than locally impacted reefs: 1) Given the growing frequency of mass bleaching I’m starting to question whether this even matters. 2) This doesn’t appear to be the case: if they did recover more quickly, coral cover should on average be greater (assuming the disturbance regime was equivalent). But it isn’t.

Leave a Reply