Every five or ten years since 1963 a growing number of wild animal and plant species have been assessed for their risk of extinction to provide hard data useful to conservation and management. The unlucky ones found to be slipping go on the “Red List” overseen by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

On land, that is.

But what about ocean wildlife — what if commercially exploited fishes were examined by the same criteria? And what would happen if, say, the majestic and obscenely valuable bluefin tuna were declared an endangered species? The answer, or part of it, is now at hand.

Tunas and billfish are some of the ocean’s biggest, most valuable, and most charismatic fishes. An expert working group recently completed the first standardized, global assessment of these fishes, using IUCN’s “Red List” criteria. Is the glass half full? Or half empty? SeaMonster investigates:

“The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is widely recognized as the most comprehensive, objective global approach for evaluating the conservation status of plant and animal species . . . and now plays an increasingly prominent role in guiding conservation activities of governments, NGOs and scientific institutions . . . [via] a scientifically rigorous approach to determine risks of extinction that is applicable to all species, [and] has become a world standard.”

The new assessment brought together more than 45 of the world’s experts on scombrids (tunas and mackerels) and billfish, including fisheries scientists, biologists, and taxonomists, to review and synthesize regional and global data for each of the world’s 61 scombrid and billfish species, and assign each species an IUCN Red List category.

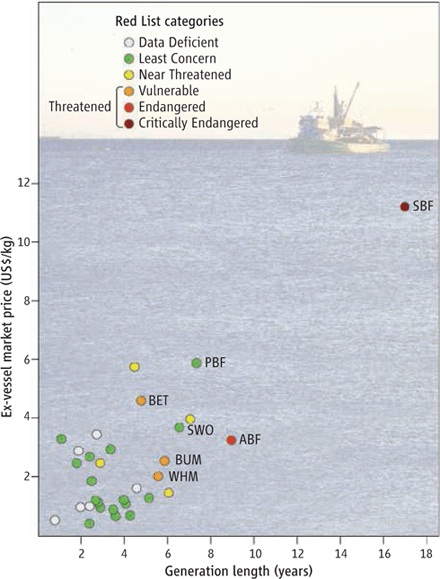

The results were published recently in Science, and concluded that seven species — or 11% — of the 61 assessed species met the IUCN criteria for a threatened category:

“Five of the seven threatened species are tuna and billfishes: southern bluefin (Thunnus maccoyii, Critically Endangered, SBF on the chart); Atlantic bluefin (T. thynnus, Endangered, ABF); bigeye tuna (T. obesus, Vulnerable, BET); blue marlin (Makaira nigricans, Vulnerable, BUM); and white marlin (Kajikia albida, Vulnerable, WHM). All have relatively long generation lengths (e.g., greater than 4.7 years) and high economic value worldwide (see the chart). “

Your intrepid reporter at SeaMonster recently sat down (virtually speaking) with three of the team members and co-authors of the Science report for some background on the study — and on how lead author and ichthyologist extraordinaire Bruce Collette got into the business:

Dr. Bruce Collette is one of the world’s leading ichthyologists and a senior scientist at the NMFS National Systematics Laboratory in Washington DC. He’s spent his career studying scombrids (tunas, bonitos, mackerels and Spanish mackerels) and billfishes (swordfish and marlins) since he joined NOAA’s Fisheries Service more than 50 years ago. Bruce led the working group that produced the evaluation and the Science paper. Bruce would not remember this but I first met him when I was a wide-eyed young lad taking a field course in Tropical Marine Invertebrates at the Bermuda Biological Station back in 1982.

Dr. Bruce Collette is one of the world’s leading ichthyologists and a senior scientist at the NMFS National Systematics Laboratory in Washington DC. He’s spent his career studying scombrids (tunas, bonitos, mackerels and Spanish mackerels) and billfishes (swordfish and marlins) since he joined NOAA’s Fisheries Service more than 50 years ago. Bruce led the working group that produced the evaluation and the Science paper. Bruce would not remember this but I first met him when I was a wide-eyed young lad taking a field course in Tropical Marine Invertebrates at the Bermuda Biological Station back in 1982.

Dr. Kent Carpenter is a Professor at Old Dominion University and Manager of the IUCN Global Marine Species Assessment (GMSA).The GMSA is completing the first global review of every marine vertebrate species, as well as a growing number of marine invertebrates like corals, and plants like seagrasses and mangroves, to determine their conservation status and extinction risk. The project involves compiling and analyzing all existing data on ~ 20,000 marine species.

Dr. Kent Carpenter is a Professor at Old Dominion University and Manager of the IUCN Global Marine Species Assessment (GMSA).The GMSA is completing the first global review of every marine vertebrate species, as well as a growing number of marine invertebrates like corals, and plants like seagrasses and mangroves, to determine their conservation status and extinction risk. The project involves compiling and analyzing all existing data on ~ 20,000 marine species.

Dr. John Graves is Chancellor Professor of Marine Science and my homie here at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. His research focuses on molecular evolution of marine organisms, particularly the population structure of big ocean fishes like billfish and tunas. Recently his group has been studying how to minimize injury to billfish released from fishing gear, and reducing bycatch in the pelagic longline fishery. John has served fishery management for many years, including as Chair of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).

Dr. John Graves is Chancellor Professor of Marine Science and my homie here at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. His research focuses on molecular evolution of marine organisms, particularly the population structure of big ocean fishes like billfish and tunas. Recently his group has been studying how to minimize injury to billfish released from fishing gear, and reducing bycatch in the pelagic longline fishery. John has served fishery management for many years, including as Chair of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).

Right. On to the interview:

Emmett: Application of the IUCN Red List criteria for large marine fishes seems eminently sensible. Why had it not been done before for commercial species – was it simply a matter of mustering the work force, or was it too politically sensitive?

Bruce: FAO and fishery scientists in general don’t agree with the IUCN criteria and I get the feeling that they don’t want us mucking about in their area of expertise, population dynamics, etc. They feel that exploitation of a virgin stock may quickly bring the spawning stock biomass down to 50-60% of the original and those are the kind of numbers that IUCN uses to indicate threatened species. I find the categories used by an FAO tuna specialist, Jacek Majkowski (2007, FAO Fish Tech. Pap. 483), to be very similar to the Red List categories we use in IUCN.

Kent: Completing Red List Assessments is extremely time consuming but it is possible to hasten the process through workshops that aggregate experts. Workshops are expensive and require fund raising. The main reason most fishes have not been assessed under Red List Criteria to date is because the process is time consuming and costly. The Global Marine Species Assessment was created in 2006 in order to make Red List assessments of marine species a priority. We have steadily been assessing marine species but fisheries species are particularly time consuming because there is so much data involved. These data need to be synthesized before an assessment can be done. So the short answer to the question is – the process only really began around 5 years ago and we are working as fast as we can!

John: Most of the major fishery species are assessed by the various RFMOs. Inasmuch as management occurs on a local (ocean basin) level, there wasn’t a major need for a global assessment. With the IUCN Global Marine Assessment, funding became available to look at the condition of these species throughout their ranges. That allowed the mustering of a work force. The topic is not that politically sensitive.

Emmett: I’ve already heard your paper used both by some parties to argue that big fish are in real trouble, and conversely by others arguing that the paper refutes earlier dire predictions and that fisheries are in better shape than we thought. What’s your take – is the glass half full, half empty, or what?

Emmett: I’ve already heard your paper used both by some parties to argue that big fish are in real trouble, and conversely by others arguing that the paper refutes earlier dire predictions and that fisheries are in better shape than we thought. What’s your take – is the glass half full, half empty, or what?

Bruce: I guess half and half. In the Science paper, we show that populations of several species that Worm and company thought were in really bad shape based on catches may not be so bad based on more accurate measures such as assessment of spawning stock biomass, etc. However, other species, like the three species of bluefin tunas are really in bad shape. The western Atlantic bluefin tuna has had its spawning stock biomass reduced by about 80% since the fishery started in the 1960s. However, most of the population dynamics people like to start their analysis in the 1970s after the population had already taken a big hit.

Kent: Our paper should be a clear indication that if fisheries managers don’t do something quickly and effectively, all tunas will go the way of the southern bluefin, the western stock of the Atlantic bluefin, and the cod. I would call that a wake-up call.

John: From my perspective, the glass is half full. If one uses the IUCN to evaluate the effectiveness of the RFMOs, they are pretty much doing their job for the target species. That would not be the case for many of the bycatch species, but then most RFMO conventions do not directly address bycatch (turtles, sharks, marine mammals, turtles, etc.). Of the species under the RFMO conventions, bluefin tuna are a problem, and that relates to their high value. Billfish, which represent an incidental catch or bycatch but are covered under the conventions, are also problem. Even though they are not targeted, they are vulnerable to longline gear, and they cannot sustain the same level of fishing pressure as the target species.

Emmett: Now that you’ve established who’s endangered and who’s not by widely accepted criteria, what are the policy implications of this work, that is, what happens next?

Bruce: We worked very hard with Science to get this paper published before Kobe 3, the meeting in La Jolla of all the RFMOs (Regional Fishery Management Agencies) in the hopes that we could influence their behavior more toward conservation measures. Listing as one of the three threatened categories on the IUCN Red List has no legal or other direct effect but many organizations use it as a guideline to develop conservation measures. Hopefully, we will be more successful in getting the Atlantic bluefin listed on CITES than we did at the meeting of the parties in Dohar last year.

John: While the IUCN criteria may be widely accepted, they were primarily developed for terrestrial organisms. Our review panel had several problems applying a “one size fits all” set of criteria to these species. In fact, we drafted a letter explaining the problems to the IUCN. As for what happens next, it seems that the RFMOs need to address the most seriously impacted fisheries (bluefin tunas and istiophorid billfishes).

Emmett: Your paper notes that the high market value of Bluefin tuna means they are likely to be hunted intensively regardless of regulations. What can be done about this – is there any hope for this species?

Bruce: When one Pacific bluefin can sell for $396,000 at a Japanese auction, it is indeed difficult to persuade fishermen that they shouldn’t hunt for even the very last Bluefin. Rarity always commands a high price in jewelry, real estate, pets, and food. For example, no directed fishing for bluefin is allowed in the Gulf of Mexico, the spawning grounds for the western Atlantic population of the species, but fishermen are allowed to bring in one bluefin caught incidental to fishing for yellowfin. But if one bluefin might be worth thousands of dollars, why not try for the one bluefin which might be worth more than the boatload of yellowfin? Listing on CITES might help because then we would have a paper trail of where any bluefin captured goes.

John: Bluefin tuna face many challenges. International management is implemented and enforced by each member nation. If a nation does not take its responsibilities seriously, there will be problems. Country-specific quotas of bluefin in the Mediterranean have been greatly reduced over the past few years, and the reductions in quota have gone hand in hand with a mandatory reduction in capacity. ICCAT reviews and approves (or disapproves) these plans. It’s a very different game these days. But falsification of government approved shipping documents and underreporting have been uncovered in some countries. Also, the unrest in northern Africa has resulted in a lack of enforcement (Libya has high catches of bluefin). These problems are being addressed, but there will be many others. There is hope for bluefin tuna, but it will take a lot of cooperation on harvesting and importing nations to stem the tide of IUU [Illegal, Unregulated, and Unreported] fish.

Emmett: People everywhere want to know what they can personally do to help the ocean. Any advice for us? Does your work highlight particular actions that individuals can take to promote sustainable oceans?

Emmett: People everywhere want to know what they can personally do to help the ocean. Any advice for us? Does your work highlight particular actions that individuals can take to promote sustainable oceans?

Bruce: Well, there is no point telling them to not eat bluefin sashimi because most of us can’t afford it! On the other hand, canned tuna is mostly OK and the International Sustainable Seafood Foundation is signing up tuna canners to only purchase tuna (mostly skipjack and yellowfin) from sustainable fishing operations. However, it will be much more difficult to persuade buyers and sellers of fresh and frozen tuna to follow suit. Several organizations issue guidelines for sustainable seafood and several big chains have responded to pressure to only offer sustainable seafood for sale. If your store doesn’t follow those guidelines, tell them that you are going to switch to a store that does follow the sustainable seafood guidelines.

Emmett: Can you tell us three of your favorite seafoods that we can eat with a clean conscience?

Bruce: Squid, canned yellowfin or skipjack (maybe not albacore), and native (not pen-reared) salmon.

Emmett: Now for a few more personal questions. How did you first become interested in sea life? Any formative experience that influenced your path into this career?

Bruce: Through grammar school, high school, and college, I was interested first in birds, then insects, and then reptiles and amphibians. When deciding on graduate school, I picked a project on the systematics of two subgenera of freshwater darters. In the summer of 1958, Bob Gibbs (a former Cornell graduate) hired me to assist him with a project on tunas and dolphinfishes at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. We went off on a couple of Bureau of Commercial Fisheries exploratory fishing cruises hunting for tuna. I greatly enjoyed my first cruises and the fantastic huge tunas that we caught – bluefin, yellowfin, bigeye, and albacore. That summer led to my first marine paper, in 1959 on dolphinfishes with Gibbs, and started our revisionary research on the large tunas of the genus Thunnus that was published in the Fishery Bulletin in 1968.

Emmett: How has your profession changed since you got into the business?

Emmett: How has your profession changed since you got into the business?

Bruce: Emphasis has gone from detailed morphological investigations to molecular research, sometimes performed by some investigators that would be unable to identify the species whose tissue they are analyzing. I still go to the library at the Smithsonian to look at new journals every day that I am in the lab. Younger professionals say they can find everything on the web but that presupposes that you know what you are looking for. I spent my summers for most of the last 40 years teaching the biology of fishes at marine stations so I need to know at least a little bit about all aspects of ichthyology. My summer teaching led me to accept Gene Helfman’s proposal to join with him in writing our textbook (the second edition of which is currently the best-selling ichthyology text in the world!)

Emmett: Any advice for young aspiring marine biologists?

Bruce: Take a course or two at a marine station. Volunteer to work in a museum or aquarium. Seek intern positions.

Emmett: Any other points you’d like to make?

Bruce: The main focus of my career has been to work out the systematics of all the scombrids so when I was asked to chair the IUCN Red List Species Specialist Group on tunas and billfishes, I could hardly refuse. It was time for me to give back to the fishes that made my career successful.

Leave a Reply